Nov 18, 2016—

Brazilian firm Oxford, the largest ceramic and porcelain manufacturer in the Americas, is owned by the three founding families of WEG, another Brazilian company and one of the largest electrical equipment manufacturers in the world. Oxford has announced that it has achieved a return on investment (ROI) in radio frequency identification following 12 months of use, thanks to a reduction to zero of errors in shipments and deliveries of goods to its customers. Marcelo Correa, Oxford's logistics andRFID project manager, officially announced this result to the company's Board of Directors this month.

Located in the small, quiet city of São Bento do Sul, in the state of Santa Catarina, Oxford has 2,500 stock-keeping units (SKUs) and manufactures six million units monthly at all of its three manufacturing plants—one of which opened in July 2016 in the Brazilian state of Espirito Santo. Once produced, the products are packed every month into 300,000 boxes, which must then be separated and delivered correctly according to each customer's request.

Oxford supplies dining appliances (plates, cups, mugs and sets of pans) throughout Brazil and abroad, and also exports its products to China. Among its customers are gift, decor and retail stores that sell ceramics and porcelain under the brand name Oxford, as well as companies that submit orders for promotional chinaware with their own brands—for example, porcelain mugs under the Starbucks Coffee brand.

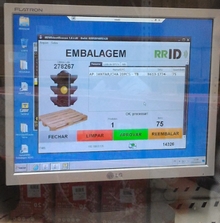

Upon leaving the factory, the goods are packed according to customers' requests, in standard boxes to fit the ordered packages. There are collections that, for example, have in a single box 12 shallow dishes, 12 soup bowls, 12 dessert plates and so on. This is where the first step ofRFID deployment comes in, as orders are routed to the packaging area with cartons and smart labels already printed on a roll.

Each box receives the label that identifies it according to its content, the number of units ordered and so forth. The packages are then forwarded to Oxford's stock area, where they are stacked in an organized and identified manner. In the passage from the packing area to the inventory area, there is an RFID portal that reads the tags, identifying the goods contained within each box. "Products can be transported by trolleys or by forklifts," Correa explains, "and are easily locatable, because the storage location is recorded by inventory employees in theERP [enterprise resource planning system]."

In addition to providing the exact location and identification of each stored item, RFIDtechnology has been used to provide speed and efficiency in the separation and routing of customers' orders. "Each order has its content CHOSE and then passes through anotherRFID portal for confirmation and routing to the five docks," Correa says, noting that prior to the RFID system's deployment, Oxford did not operate on docks. "One of the gains of the technology deployment was to make us better organize the company's processes."

Each dock is operated by one of the carriers that provides services to Oxford. "Dish boxes are placed inside the docks," Correa states, "and each carrier can check the orders it has, to deliver them more easily than before RFID."

With the introduction of the technology, Oxford was able to eliminate an extra source of costs, which mainly involved the setback logistics of improperly delivered goods. "The costs generated by these corrections in the deliveries were enough to finance the entire RFIDproject in just one year of use," Correa says, adding that RFID has created a new level of demand and quality that was achieved with a year of studies and then after another year of operation.

"From next year, I'll put my foot on the road," Correa says. "In 2017, I will help make carriers understand the gains they can have if they deploy RFID readers in their processes to improve this stage of distribution." Since the porcelain manufacturer has already installedRFID tags throughout its operations, everything is ready for the transporters to gain more efficiency in separating and delivering the orders.

Correa reports that prior to RFID's use, production tracking was accomplished by scanning bar codes and addressing the storage-management system (WMS), via manual reports that contained many errors. "The shipment was done with visual control and shipping labels," he explains. "With RFID, production was automated 100 percent… and every shipment passes through a portal that checks if the products confer with the invoice informed."

RFID deployment complies with GS1's passive EPC ultrahigh-frequency (UHF) RFIDstandard, Correa says, because he understands that adherence to standards facilitates deployments. There are two fixed readers installed in each of the two portals, one at the stock entrance and another in the shipment area. "Addressing in the WMS is done by tablets," he says, "and the collectors will be used for inventory and shipping in other units."

Among the devices, readers are provided by Impinj and Identix (Core Impinj), antennas are supplied by Laird and Identix, collectors are from mobile phone brand (acquired by Zebra Technologies) and printers are also provided by Zebra. The tags use Impinj's E52 Monza5 and Monza R6 inlays, made by Brazilian vendors such as CCRR. According to Correa, the gains achieved with RFID met all expectations, resulting in improved production precision and a reduction in shipment errors.

"This RFID use case shows that the technology is no longer just a test—it is RFID beyond pilots," says engineer Roberto Cordeiro, an executive with more than 35 years of experience in the business-to-business and business-to-consumer technology markets who, with fellow engineer Ricardo Monteiro, founded Parson RFID. "RFID has helped improve employee behavior at the pallet-making and -shipping levels."

Parson has developed solutions for RFID portals with a high level of engineering, Cordeiro reports. "When we passed the boxes through the portals,RFID readers read everything that was around them, including what was not to be read, because we wanted to identify only what was inside theportal," he says. "To prevent this from happening, we had to calibrate the readers with Identix technology and developed an innovation: a waveattenuator that causes RFID transmissions to weaken at the portal's entrance and exit, preventing the reading of tags outside the place where the products are to be identified." The portals are actually Faraday cages with the Parson attenuators at their ends.

Oxford's RFID project has evolved so positively that the company has begun coming up with ideas regarding where to use radio frequency identification tags in the future. Correa imagines, for example, a dish with an inlay and an RFID antenna inserted in its base, through a cavity and covered with a special resin. The plate is ready, he says—it has been manufactured and is currently being tested. The purpose of this new product will be to meet specific usage needs. "We have customers who are restaurants, for example, who need standardized dishes with equal weights," Correa explains. "If the tag has information about the exact weight of the dish, [a company can] just have a scale with an RFID reader to give only the volume of food contained in the container with precision and accuracy."

Innovation and learning are in Oxford's DNA, Cordeiro says, as the company produces its own ceramic and porcelain manufacturing machines, while also mining and processing the raw materials used to make dishes. In addition, the solutions developed by Parson are also innovative and replicable in other market segments. "Adaptations and the meeting of new processes were primarily responsible for the success of the RFID deployment at Oxford," he states, "since it is almost impossible to get the adherence of a new technology to existing processes without modifying them."